There are popular mainstream beliefs that are just plain wrong.

One of them, is the issue I shall address: Sailbacked Spinosaurs.

Spinosaurus has traditionally been depicted with a sail. Jurassic Park 3 is also to blame for this as well.

But just because it's depicted as such, doesn't mean it's true. In fact, it's in this case, it's pretty wrong.

The comparisons used to give Spinosaurus a sail are Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus, they even literally put a Dimetrodon sail on a spinosaurid's body in some reconstructions, like the one shown below:

|

| Spinosaurus does NOT look like this! |

Whoever made that depiction, obviously did not look at, or completely ignored, the fossils.

|

| Spinosaurus holotype IPHG 1912. Note the broadness of the spines, and the fact that they look nothing like that of Dimetrodon. |

By looking at the fossils, it's pretty obvious that Spinosaurus' neural spines looked nothing like a sailback's. In fact, Spinosaurus spines actually resemble bison and chameleon spines more(not perfect matches though) than those pathetic thin rods.

|

| Chamaleo melleri, in the flesh. There is no clear distinction between ridge and back. |

The dorsal structure of Spinosaurus seems to possess attributes of both bison and chameleon spines. It is therefore likely that Spinosaurus had a ridge. It would have looked like a vertically-elongated triangle with a somewhat thin and rounded top in cross-section.

The neural spines of sailbacks only have to support itself and a vascular network. They can, and do get thinner distally, from all directions. This is not the case with Spinosaurus.

No suitable comparison can give Spinosaurus a skin sail.

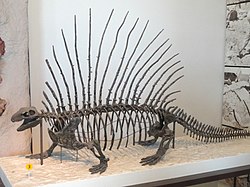

Oh, and here's the Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus stuff:

|

| Dimetrodon skeleton. Note the thin rod-like spines, which look absolutely NOTHING like the ones found in Spinosaurus. |

| |

| Edaphosaurus skeleton. Again, a total lack of resemblance to the spines of Spinosaurus. |

Those sailbacks have spines which, aside from being long and elongated, have nothing in common with that of Spinosaurus!

In the top image, I have photoshopped a Spinosaurus restoration, to incorporate the more likely dorsal structures. The same has been done with the Ouranosaurus carcass. Here is the original, and very wrong, image.

Whether that structure is muscle or fat remains is still debatable.

With this, we can say, that a Dimetrodon-backed Spinosaurus is silliness.

If it had a sail, why would it evolve broad spines, when thin rods could have done the job?

Simple answer: It did NOT evolve a sail. Animals do not waste energy developing useless structures.